Alvin York

![]()

Alvin York

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia jump to navigationJump to search“Sergeant York” redirects here. For other uses, see Sergeant York (disambiguation).

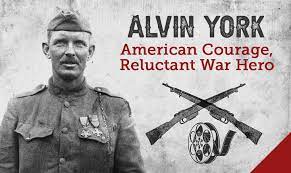

| Alvin C. York | |

|---|---|

| York in uniform, 1919, wearing the Medal of Honor and French Croix de Guerre with Palm | |

| Birth name | Alvin Cullum York |

| Nickname(s) | “Sergeant York” |

| Born | December 13, 1887 Fentress County, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | September 2, 1964 (aged 76) Nashville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Buried | Wolf River Cemetery, Pall Mall, Tennessee, U.S.  36°32′50.2″N 84°57′14.8″W 36°32′50.2″N 84°57′14.8″W |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/branch | United States ArmyTennessee State Guard |

| Years of service | 1917–1919 (active)1942–1945 (honorary)1941–1947 (State Guard) |

| Rank | Sergeant (active)Major (Hon.)Colonel (Tenn.) |

| Service number | 1910421 |

| Unit | Company G, 328th Infantry, 82nd Division (1917–1919)U.S. Army Signal Corps (1942–1945) |

| Commands held | 7th Regiment, Tennessee State Guard (1941–1947) |

| Battles/wars | World War IBattle of Saint-MihielMeuse-Argonne OffensiveDefensive SectorWorld War IIAmerican Theater |

| Awards | Medal of Honor1914–1918 War Cross with Palm (France)See more |

| Spouse(s) | Gracie Loretta Williams(m. 1919) |

| Children | 10 |

| Other work | Superintendent of the Cumberland Mountain State Park |

| Website | sgtyork.org |

Alvin Cullum York (December 13, 1887 – September 2, 1964), also known as Sergeant York, was one of the most decorated United States Army soldiers of World War I.[1] He received the Medal of Honor for leading an attack on a German machine gun nest, gathered 35 machine guns, killing at least 25[2] enemy soldiers and capturing 132 prisoners. York’s Medal of Honor action occurred during the United States-led portion of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in France, which was intended to breach the Hindenburg line and force the Germans to surrender. He earned decorations from several allied countries during WWI, including France, Italy and Montenegro.

York was born in rural Tennessee, in what is now the community of Pall Mall in Fentress County. His parents farmed, and his father worked as a blacksmith. The eleven York children had minimal schooling because they helped provide for the family, including hunting, fishing, and working as laborers. After the death of his father, York assisted in caring for his younger siblings and found work as a blacksmith. Despite being a regular churchgoer, York also drank heavily and was prone to fistfights. After a 1914 conversion experience, he vowed to improve and became even more devoted to the Church of Christ in Christian Union. York was drafted during World War I; he initially claimed conscientious objector status on the grounds that his religious denomination forbade violence. Persuaded that his religion was not incompatible with military service, York joined the 82nd Division as an infantry private and went to France in 1918.

In October 1918, Private First Class (Acting Corporal) York was one of a group of seventeen soldiers assigned to infiltrate German lines and silence a machine gun position. After the American patrol had captured a large group of enemy soldiers, German small arms fire killed six Americans and wounded three. Several of the Americans returned fire while others guarded the prisoners. York and the other Americans attacked the machine gun position, killing several German soldiers.[3] The German officer responsible for the machine gun position had emptied his pistol while firing at York but failed to hit him. This officer then offered to surrender and York accepted. York and his men marched back to their unit’s command post with more than 130 prisoners. York was later promoted to sergeant and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. An investigation resulted in the upgrading of the award to the Medal of Honor. York’s feat made him a national hero and international celebrity among allied nations.

After Armistice Day, a group of Tennessee businessmen purchased a farm for York, his new wife, and their growing family. He later formed a charitable foundation to improve educational opportunities for children in rural Tennessee. In the 1930s and 1940s, York worked as a project superintendent for the Civilian Conservation Corps and managed construction of the Byrd Lake reservoir at Cumberland Mountain State Park, after which he served for several years as park superintendent. A 1941 film about his World War I exploits, Sergeant York, was that year’s highest-grossing film; Gary Cooper won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of York, and the film was credited with enhancing American morale as the US mobilized for action in World War II. In his later years, York was confined to bed by health problems. He died in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1964 and was buried at Wolf River Cemetery in his hometown of Pall Mall, Tennessee.

Contents

- 1Early life and ancestry

- 2World War I

- 3Homecoming and fame

- 4After the war

- 5Personal life and death

- 6Awards

- 7Legacy

- 8See also

- 9Notes

- 10References

- 11Further reading

- 12External links

Early life and ancestry[edit]

Alvin Cullum York was born in a two-room log cabin in Fentress County, Tennessee.[4] He was the third child born to William Uriah York and Mary Elizabeth (Brooks) York. William Uriah York was born in Jamestown, Tennessee, to Uriah York and Eliza Jane Livingston, who had moved to Tennessee from Buncombe County, North Carolina.[5] Mary Elizabeth York was born in Pall Mall to William Brooks, who took his mother’s maiden name as an alias of William H. Harrington after deserting from Company A of the 11th Michigan Cavalry Regiment during the American Civil War, and Nancy Pyle, and was the great-granddaughter of Conrad “Coonrod” Pyle, an English settler who settled Pall Mall, Tennessee.

William York and Mary Brooks married on December 25, 1881, and had eleven children: Henry Singleton, Joseph Marion, Alvin Cullum, Samuel John, Albert, Hattie, George Alexander, James Preston, Lillian Mae, Robert Daniel, and Lucy Erma.[5] The York family is mainly of English ancestry, with Scots-Irish ancestry as well.[6][7] The family resided in the Indian Creek area of Fentress County.[5] The family was impoverished, with William York working as a blacksmith to supplement the family’s income. The men of the York family farmed and harvested their own food, while the mother made all of the family’s clothing.[5] The York sons attended school for only nine months[4] and withdrew from education because William York needed them to help work on the family farm, hunt, and fish to help feed the family.[5] When William York died in November 1911, his son Alvin helped his mother raise his younger siblings.[5] Alvin was the oldest sibling still residing in the county, since his two older brothers had married and relocated. To supplement the family’s income, York worked in Harriman, Tennessee,[4] first in railroad construction and then as a logger. By all accounts, he was a skilled laborer who was devoted to the welfare of his family, and a crack shot. York was also a violent alcoholic prone to fighting in saloons. In one of the saloon fights his best friend was killed. York also accumulated several arrests within the area.[4] His mother, a member of a pacifist Protestant denomination, tried to persuade York to change his ways.[8]

World War I[edit]

Conscientious Objector Claim of Appeal for Alvin Cullum York (1917)

Despite his history of drinking and fighting, York attended church regularly and often led the hymn singing. A revival meeting at the end of 1914 led him to a conversion experience on January 1, 1915. His congregation was the Church of Christ in Christian Union, a Protestant denomination that shunned secular politics and disputes between Christian denominations.[9] This church had no specific doctrine of pacifism but it had been formed in reaction to the Methodist Episcopal Church, South‘s support of slavery, including armed conflict during the American Civil War, and it opposed all forms of violence.[10] In a lecture later in life, York reported his reaction to the outbreak of World War I: “I was worried clean through. I didn’t want to go and kill. I believed in my Bible.”[11]

On June 5, 1917, at the age of 29, Alvin York registered for the draft as all men between 21 and 30 years of age were required to do as a result of the Selective Service Act. When he registered for the draft, he answered the question “Do you claim exemption from draft (specify grounds)?” by writing “Yes. Don’t Want To Fight.”[12] When his initial claim for conscientious objector status was denied, he appealed.[13] During World War I, conscientious objector status did not exempt the objector from military duty. Such individuals could still be drafted and were given assignments that did not conflict with their anti-war principles. In November 1917, while York’s application was considered, he was drafted and began his army service at Camp Gordon, Georgia.[14]

From the day he registered for the draft until he returned from the war on May 29, 1919, York kept a diary of his activities. In his diary, York wrote that he refused to sign documents provided by his pastor seeking a discharge from the Army on religious grounds and similar documents provided by his mother asserting a claim of exemption as the sole support of his mother and siblings. Despite his initial, signed request for an exemption, he later disclaimed ever having been a conscientious objector.[15]

Entry into service[edit]

York served in Company G, 328th Infantry, 82nd Division. Deeply troubled by the conflict between his pacifism and his training for war, he spoke at length with his company commander, Captain Edward Courtney Bullock Danforth Jr. (1894–1974) of Augusta, Georgia, and his battalion commander, Major G. Edward Buxton of Providence, Rhode Island, a devout Christian himself. Biblical passages about violence (“He that hath no sword, let him sell his cloak and buy one.” “Render unto Caesar …” “… if my kingdom were of this world, then would my servants fight.”) cited by Danforth persuaded York to reconsider the morality of his participation in the war. Granted a 10-day leave to visit home, he returned convinced that God meant for him to fight and would keep him safe, as committed to his new mission as he had been to pacifism.[14][16] He served with his division in the St. Mihiel Offensive.

Medal of Honor action[edit]

328th Infantry Regiment line of advance in capture of Hill 223, October 7, 1918, 82nd Division, Argonne Forest, France. (World War I Signal Corps Collection)

In an October 8, 1918, attack that occurred during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, York’s battalion aimed to capture German positions near Hill 223 (49.28558°N 4.95242°E) along the Decauville railroad north of Chatel-Chéhéry, France. His actions that day earned him the Medal of Honor.[17] He later recalled:

The Germans got us, and they got us right smart. They just stopped us dead in our tracks. Their machine guns were up there on the heights overlooking us and well hidden, and we couldn’t tell for certain where the terrible heavy fire was coming from … And I’m telling you they were shooting straight. Our boys just went down like the long grass before the mowing machine at home. Our attack just faded out … And there we were, lying down, about halfway across [the valley] and those German machine guns and big shells getting us hard.[18]

Under the command of Cpl. (Acting Sergeant) Bernard Early, four non-commissioned officers, including Acting Corporal York,[19] and thirteen privates were ordered to infiltrate the German lines to take out the machine guns. The group worked their way behind the Germans and overran the headquarters of a German unit, capturing a large group of German soldiers who were preparing a counter-attack against the U.S. troops. Early’s men were contending with the prisoners when German machine gun fire suddenly peppered the area, killing six Americans and wounding three others. Several of the Americans returned fire while others guarded the prisoners. From his advantageous position, York fought the Germans.[20] York recalled:

And those machine guns were spitting fire and cutting down the undergrowth all around me something awful. And the Germans were yelling orders. You never heard such a racket in all of your life. I didn’t have time to dodge behind a tree or dive into the brush … As soon as the machine guns opened fire on me, I began to exchange shots with them. There were over thirty of them in continuous action, and all I could do was touch the Germans off just as fast as I could. I was sharp shooting … All the time I kept yelling at them to come down. I didn’t want to kill any more than I had to. But it was they or I. And I was giving them the best I had.[21]

Sergeant Alvin C. York by Frank Schoonover, 1919

During the assault, a German officer led several Germans to the scene of the fighting and ran into York who shot several of them with his pistol.[22]

Imperial German Army First Lieutenant Paul Jürgen Vollmer, commanding the 120th Reserve Infantry Regiment’s 1st Battalion, emptied his pistol trying to kill York while he was contending with the machine guns. Failing to injure York, and seeing his mounting losses, he offered in English to surrender the unit to York who accepted.[23] At the end of the engagement, York and his seven men marched their German prisoners back to the American lines. Upon returning to his unit, York reported to his brigade commander, Brigadier General Julian Robert Lindsey, who remarked: “Well York, I hear you have captured the whole German army.” York replied: “No sir. I got only 132.”

York’s actions silenced the German machine guns and were responsible for enabling the 328th Infantry to renew its attack to capture the Decauville Railroad.[24]

Post-battle[edit]

Sergeant Alvin C. York at the hill where his actions earned him the Medal of Honor (February 7, 1919)

York was promptly promoted to sergeant and received the Distinguished Service Cross. A few months later, an investigation by York’s chain of command resulted in an upgrade of his Distinguished Service Cross to the Medal of Honor, which was presented by the commanding general of the American Expeditionary Forces, General John J. Pershing. The French Republic awarded him the Croix de Guerre, Medaille Militaire and Legion of Honor.

In addition to his French medals, Italy awarded York the Croce al Merito di Guerra and Montenegro decorated him with its War Medal.[2][25] He eventually received nearly 50 decorations.[2] York’s Medal of Honor citation reads:[26]

After his platoon suffered heavy casualties and 3 other noncommissioned officers had become casualties, Cpl. York assumed command. Fearlessly leading seven men, he charged with great daring a machine gun nest which was pouring deadly and incessant fire upon his platoon. In this heroic feat the machine gun nest was taken, together with 4 officers and 128 men and several guns.

In attempting to explain his actions during the 1919 investigation that resulted in the Medal of Honor, York told General Lindsey “A higher power than man guided and watched over me and told me what to do.” Lindsey replied “York, you are right.”[27]

Biographer David D. Lee (2000) wrote:

Initially York’s exploit attracted little public attention, but on 26 April 1919, Saturday Evening Post correspondent George Pattullo published “The Second Elder Gives Battle,” an account of the firefight that made York a national hero overnight. York’s explanation that God had been with him during the fight meshed neatly with the popular attitude that American involvement in the war was truly a holy crusade, and he returned to the United States in the spring of 1919 amid a tumultuous public welcome and a flood of business offers from people eager to capitalize on the soldier’s reputation.[28]

Homecoming and fame[edit]

Before leaving France, York was his division’s noncommissioned officer delegate to the caucus which created the American Legion, of which York was a charter member.[29]U.S. Army Sergeant Alvin C. York after his return to his Tennessee home. His mother is pouring water into the basin and his younger sister is standing on the cabin’s back porch. York turned down many lucrative offers, including one worth $30,000 (equivalent to $469,000 in 2021) to appear in vaudeville, to return to the life he had known before the war.[30]

York’s heroism went unnoticed in the United States press, even in Tennessee, until the publication of the April 26, 1919, issue of the Saturday Evening Post, which had a circulation in excess of 2 million. In an article titled “The Second Elder Gives Battle”, journalist George Pattullo, who had learned of York’s story while touring battlefields earlier in the year, laid out the themes that have dominated York’s story ever since: the mountaineer, his religious faith and skill with firearms, patriotic, plainspoken and unsophisticated, an uneducated man who “seems to do everything correctly by intuition.”[31] In response, the Tennessee Society, a group of Tennesseans living in New York City, arranged celebrations to greet York upon his return to the United States, including a 5-day furlough to allow for visits to New York City and Washington, D.C. York arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey, on May 22, stayed at the Waldorf Astoria, and attended a formal banquet in his honor. He toured the subway system in a special car before continuing to Washington, where the House of Representatives gave him a standing ovation and he met Secretary of War Newton D. Baker and the President’s secretary Joe Tumulty, as President Wilson was still in Paris.[32]

York proceeded to Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, where he was discharged from the service, and then to Tennessee for more celebrations. He had been home for barely a week when, on June 7, 1919, York and Gracie Loretta Williams were married by Tennessee Governor Albert H. Roberts in Pall Mall. More celebrations followed the wedding, including a week-long trip to Nashville where York accepted a special medal awarded by the state.[33]

York refused many offers to profit from his fame, including thousands of dollars offered for appearances, product endorsements, newspaper articles, and movie rights to his life story. Instead, he lent his name to various charitable and civic causes.[34] To support economic development, he campaigned for the Tennessee government to build a road to service his native region, succeeding when a highway through the mountains was completed in the mid-1920s and named Alvin C. York Highway.[35] The Nashville Rotary organized the purchase, by public subscription, of a 400-acre (1.6 km2) farm, the one gift that York accepted. However, it was not the fully equipped farm he was promised, requiring York to borrow money to stock it. He subsequently lost money in the farming depression that followed the war. Then the Rotary was unable to continue the installment payments on the property, leaving York to pay them himself. In 1921, he had no option but to seek public help, resulting in an extended discussion of his finances in the press, some of it sharply critical. Debt in itself was a trial: “I could get used to most any kind of hardship, but I’m not fitted for the hardship of owing money.” Only an appeal to Rotary Clubs nationwide and an account of York’s plight in the New York World brought in the required contributions by Christmas 1921.[36]

After the war[edit]

In the 1920s, York formed the Alvin C. York Foundation with the mission of increasing educational opportunities in his region of Tennessee. Board members included the area’s congressman, Cordell Hull, who later became Secretary of State under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Secretary of the Treasury William G. McAdoo, who was President Wilson‘s son-in-law, and Tennessee Governor Albert Roberts. Plans called for a non-sectarian institution providing vocational training to be called the York Agricultural Institute. York concentrated on fund-raising, though he disappointed audiences who wanted to hear about the Argonne when he instead explained that “I occupied one space in a fifty mile front. I saw so little it hardly seems worthwhile discussing it. I’m trying to forget the war in the interest of the mountain boys and girls that I grew up among.”[37] He fought first to win financial support from the state and county, then battled local leaders about the school’s location. Refusing to compromise, he resigned and developed plans for a rival York Industrial School. After a series of lawsuits he gained control of the original institution and was its president when it opened in December 1929. As the Great Depression deepened, the state government failed to provide promised funds, and York mortgaged his farm to fund bus transportation for students. Even after he was ousted as president in 1936 by political and bureaucratic rivals, he continued to donate money.[38][39]Alvin C. York after World War I

In 1935 York, sensing the end of his time with the institute, began to work as a project superintendent with the Civilian Conservation Corps overseeing the creation of Cumberland Mountain State Park‘s Byrd Lake, one of the largest masonry projects the program ever undertook.[40] York served as the park’s superintendent until 1940.[41] In the second half of 1930s and early 1940s, in the run-up to the America’s entry in World War II, York was a forceful and public advocate for interventionism, calling for U.S. involvement in the war against Germany, Italy and Japan.[42] At the time, U.S. public opinion was overwhelmingly in favor of the isolationist and non-interventionist approach, and York’s unpopular views led to accusations that he was engaged in war-mongering. York became a relatively rare high-profile public voice for intervention. In a speech at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in May 1941, York said: “We must fight again! The time is not now ripe, nor will it ever be, to compromise with Hitler, or the things he stands for.”[42]

York’s speeches attracted the attention of President Roosevelt, who frequently quoted York, particularly a passage from York’s Tomb of the Unknown Soldier speech:

By our victory in the last war, we won a lease on liberty, not a deed to it. Now after 23 years, Adolf Hitler tells us that lease is expiring, and after the manner of all leases, we have the privilege of renewing it, or letting it go by default … . We are standing at the crossroads of history. The important capitals of the world in a few years will either be Berlin and Moscow, or Washington and London. I, for one, prefer Congress and Parliament to Hitler’s Reichstag and Stalin’s Kremlin. And because we were for a time, side by side, I know this Unknown Soldier does too. We owe it to him to renew that lease of liberty he helped us to get.[42]

During World War II, York attempted to re-enlist in the Army.[43][44] However, at fifty-four years of age, overweight,[43] near-diabetic,[45] and with evidence of arthritis, he was denied enlistment as a combat soldier. Instead, he was commissioned as a major in the Army Signal Corps[43][45] and he toured training camps and participated in bond drives in support of the war effort, usually paying his own travel expenses. Gen. Matthew Ridgway later recalled that York “created in the minds of farm boys and clerks … the conviction that an aggressive soldier, well-trained and well-armed, can fight his way out of any situation.” He also raised funds for war-related charities, including the Red Cross. He served on his county draft board and, when literacy requirements forced the rejection of large numbers of Fentress County men, he offered to lead a battalion of illiterates himself, saying they were “crack shots”.[46] Although York served during the war as a Signal Corps major[43][45] and as a colonel with the 7th Regiment of the Tennessee State Guard,[47] newspapers continued to refer to him as “Sergeant York”.[48]

Legacy and film story[edit]

Biographer David Lee explored the reason Americans responded so favorably to his story:

York’s Appalachian heritage was central to his popularity because the media portrayed him as the archetypical mountain man. At a time of domestic upheaval and international uncertainty, York’s pioneer-like skill with a rifle, his homespun manner, and his fundamentalist piety endeared him to millions of Americans as a “contemporary ancestor” fresh from the backwoods of the southern mountains. As such, he seemed to affirm that the traditional virtues of the agrarian United States still had meaning in the new era. York represented not what Americans were but what they wanted to think they were. He lived in one of the most rural parts of the country when a majority of Americans lived in cities; he rejected riches when the tenor of the nation was crassly commercial; he was pious when secularism was on the rise. For millions of people, York was the incarnation of their romanticized understanding of the nation’s past when men and women supposedly lived plainer, sterner, and more virtuous lives. Ironically, while York endured as a symbol of an older America, he spent most of his adult life working to bring roads, schools, and industrial development to the mountains, changes that were destroying the society he had come to represent.[28]

1919 newspaper coverage of Alvin York (left) with his mother and his wife, Gracie Williams

York cooperated with journalists in telling his life story twice in the 1920s. He allowed Nashville-born freelance journalist Sam Cowan to see his diary and submitted to interviews. The resulting 1922 biography focused on York’s Appalachian background, describing his upbringing among the “purest Anglo-Saxons to be found today”, emphasizing popular stereotypes without bringing the man to life.[49][50] A few years later, York contacted a publisher about an edition of his war diary, but the publisher wanted additional material to flesh out the story. Then Tom Skeyhill, an Australian-born veteran of the Gallipoli campaign,[51] visited York in Tennessee and the two became friends. On York’s behalf, Skeyhill wrote an “autobiography” in the first person and was credited as the editor of Sergeant York: His Own Life Story and War Diary. With a preface by Newton D. Baker, Secretary of War in World War I, it presented a one-dimensional York supplemented with tales of life in the Tennessee mountains.[52] Reviews noted that York only promoted his life story in the interest of funding educational programs: “Perhaps York’s bearing after his famous exploit in the Argonne best reveals his native greatness. … He will not exploit himself except for his own people. All of which gives his book an appeal beyond its contents.”[53]

The mountaineer persona Cowan and Skeyhill promoted reflected York’s own beliefs. In a speech at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, he said:

We, the descendants of the pioneer long hunters of the mountains, have been called Scotch-Irish and pure Anglo-Saxon, and that is complimentary, I reckon. But we want the world to know that we are Americans. The spiritual environment and our religious life in the mountains have made our spirit wholly American, and that true pioneer American spirit still exists in the Tennessee mountains. Even today, I want you all to know, with all the clamor of the world and its evil attractions, you still find in the little humble log cabins in the Tennessee mountains that old-fashioned family altar of prayer—the same that they used to have in grandma’s and grandpa’s day—which is the true spirit of the long hunters. We in the Tennessee mountains are not transplanted Europeans; every fiber in our body and every emotion in our hearts is American.[54]

For many years, York employed a secretary, Arthur S. Bushing, who wrote the lectures and speeches York delivered. Bushing prepared York’s correspondence as well. Like the works of Cowan and Skeyhill, words commonly ascribed to York, though doubtless representing his thinking, were often composed by professional writers.[55] York had refused several times to authorize a film version of his life story.[56] Finally, in 1940, as York was looking to finance an interdenominational Bible school, he yielded to a persistent Hollywood producer and negotiated the contract himself.[57] In 1941 the movie Sergeant York, directed by Howard Hawks with Gary Cooper in the title role, told about his life and Medal of Honor action.[58] The screenplay included much fictitious material though it was based on York’s Diary.[59][60] The marketing of the film included a visit by York to the White House where FDR praised the film.[61] Some of the response to the film divided along political lines, with advocates of preparedness and aid to Great Britain enthusiastic (“Hollywood’s first solid contribution to the national defense”, said Time) and isolationists calling it “propaganda” for the administration.[62][63] It received 11 Oscar nominations and won two, including the Academy Award for Best Actor for Cooper. It was the highest-grossing picture of 1941.[59][64] York’s earnings from the film, about $150,000 in the first two years as well as later royalties, resulted in a decade-long battle with the Internal Revenue Service.[65] York eventually built part of his planned Bible school, which hosted 100 students until the late 1950s.[66]

Political views[edit]

York originally believed in the morality of America’s intervention in World War I.[67] By the mid-1930s, he looked back more critically: “I can’t see that we did any good. There’s as much trouble now as there was when we were over there. I think the slogan ‘A war to end war’ is all wrong.”[68] He fully endorsed American preparedness, but showed sympathy for isolationism by saying that he would fight only if war came to America.[69]

A consistent Democrat – “I’m a Democrat first, last, and all the time”,[70] he said – in January 1941 he praised FDR‘s support for Great Britain and in an address at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier on Memorial Day of that year he attacked isolationists and said that veterans understood that “liberty and freedom are so very precious that you do not fight and win them once and stop.” They are “prizes awarded only to those peoples who fight to win them and then keep fighting eternally to hold them!”[71] At times he was blunt: “I think any man who talks against the interests of his own country ought to be arrested and put in jail, not excepting senators and colonels.” Everyone knew that the colonel in question was Charles Lindbergh.[72]

In the late 1940s he called for toughness in dealing with the Soviet Union and did not hesitate to recommend using the atomic bomb in a first strike: “If they can’t find anyone else to push the button, I will.”[73] He questioned the failure of United Nations forces to use the atomic bomb in Korea.[73] In the 1960s he criticized Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara‘s plans to reduce the ranks of the National Guard and reserves: “Nothing would please Khrushchev better.”[74]

Personal life and death[edit]

The graves of Alvin (right) and Gracie (left) York at Wolf River Cemetery, Pall Mall, Tennessee

York and his wife Grace had ten children, seven sons and three daughters, most named after American historical figures: Infant son (1920, died at 4 days), Alvin Cullum, Jr. (1921–1983), George Edward Buxton (1923–2018), Woodrow Wilson (1925–1998), Samuel Huston (1928–1929), Andrew Jackson (born 1930), Betsy Ross (born 1933), Mary Alice (1935–1991), Thomas Jefferson (1938–1972), and Infant daughter (1940, died same day).[75][76] His son, Thomas Jefferson was killed in the line of duty on May 7, 1972, while serving as a Constable in Fentress County, Tennessee.[77]

York suffered from health problems throughout his life. He had gallbladder surgery in the late 1920s and suffered from pneumonia in 1942. Described in 1919 as a “red-haired giant with the ruddy complexion of the outdoors” and “standing more than 6 feet … and tipping the scale at more than 200 pounds”,[78] by 1945 he weighed 250 pounds and in 1948 he had a stroke. More strokes and another case of pneumonia followed, and he was confined to bed from 1954, further handicapped by failing eyesight. He was hospitalized several times during his last two years.[79][80] York died at the Veterans Hospital in Nashville, Tennessee, on September 2, 1964, of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 76. After a funeral service in his Jamestown church, with Gen. Matthew Ridgway representing President Lyndon Johnson,[81] York was buried at the Wolf River Cemetery in Pall Mall. His funeral sermon was delivered by Richard G. Humble, General Superintendent of the Churches of Christ in Christian Union.[82] Humble also preached Mrs. York’s funeral sermon in 1984.[83]

Awards[edit]

York was the recipient of the following awards:

Legacy[edit]

Controversy[edit]

Beginning soon after York’s return to the United States at the end of the war, doubt and controversy periodically surfaced over whether the events detailed in his Medal of Honor documents had taken place as officially described, and whether other soldiers in York’s unit should also have been recognized for their heroism.[84][85] Otis Merrithew (William Cutting) and Bernard Early were among those who argued against the official version.[86] Of the 17 American soldiers who were involved in York’s Medal of Honor action, six were killed.[87] York received the Medal of Honor, and over the years, three of the others who lived through that day’s fighting also received valor awards,[88] including the Distinguished Service Cross for Early in 1929,[89] and the Silver Star for Merrithew in 1965.[90]

Discovery of ‘lost’ battlefield[edit]

Near the Chatel-Chéhéry battlefield in 2010

In October 2006, United States Army Colonel Douglas Mastriano, head of the Sergeant York Discovery Expedition (SYDE), conducted research to locate the York battle site.[91] Among the Mastriano expedition’s finds were 46 American rifle rounds.[92] In addition, his research located pieces of German ammunition and weaponry.[93] Without the official support of the French government, Mastriano excavated the site and bulldozed the area in order to build two monuments and a historic trail.[94]

However, another team lead by Dr. Tom Nolan, head of the Sergeant York Project and a geographer at the R.O. Fullerton Laboratory for Spatial Technology at Middle Tennessee State University, placed the site 600 meters south of the location identified by Mastriano.[95][96][97] Nolan’s research relied on contemporary army graves registration Forms, the 82nd Division’s wartime history, and maps drawn by G.E. Buxton and Captain E.C.B. Danforth, both of whom walked the ground with York during the Medal of Honor investigation.[98]

Monuments and memorials[edit]

Many places and monuments throughout the world have been named in honor of York, most notably his farm in Pall Mall, which is now open to visitors as the Sgt. Alvin C. York State Historic Park.

Several government buildings have been named for York, including the Alvin C. York Veterans Hospital located in Murfreesboro.[99]

The Alvin C. York Institute was founded in 1926 as a agricultural high school by York and residents of Fentress County and continues to serve as Jamestown’s high school.[100]

York Avenue on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, New York City was named for York in 1928.[101]

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Robert Penn Warren used York as the model for characters in two of his novels, both explorations of the burden of fame faced by battlefield heroes in peacetime. In At Heaven’s Gate (1943), a Tennessee mountaineer who was awarded the Medal of Honor in World War I returns from combat, becomes a state legislator, and then a bank president. Others exploit his decency and fame for their own selfish ends as the novel explores the real-life experience of an old-fashioned hero in a cynical world. In The Cave (1959), a similar hero from a similar background has aged and become an invalid. He struggles to maintain his identity as his real self diverges from the robust legend of his youth.[102]

A monumental statue of York by sculptor Felix de Weldon was placed on the grounds of the Tennessee State Capitol in 1968.[103]

In the 1980s, the United States Army named its DIVAD weapon system “Sergeant York”; the project was cancelled because of technical problems and cost overruns.[104]

In 1993, York was among 35 Medal of Honor recipients whose portraits were painted and biographies included in a boxed set of “Congressional Medal of Honor Trading Cards,” issued by Eclipse Enterprises under license from the Medal of Honor Society. The text is by Kent DeLong, the paintings by Tom Simonton, and the set edited by Catherine Yronwode.[105]

On May 5, 2000, the United States Postal Service issued the “Distinguished Soldiers” stamps, one of which honored York.[106]

The riderless horse in the 2004 funeral procession of President Ronald Reagan was named Sergeant York.[107] Laura Cantrell‘s 2005 song “Old Downtown” talks about York in depth.[108]

In 2007, the 82nd Airborne Division‘s movie theater at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, was named York Theater.[109]

The traveling American football trophy between UT Martin, Austin Peay, Tennessee State, and Tennessee Tech is called the Alvin C. York trophy.[110][111]

The U.S. Army ROTC‘s Sergeant York Award is presented to cadets who excel in the program and devote additional time and effort to maintaining and expanding it.[112]

A memorial to graduates of the East Tennessee State University ROTC program who have given their lives for their country carries a quotation from York.[113]

The Third Regiment of the Tennessee State Guard is named for York.[114]

The Association of the United States Army published a digital graphic novel about York in 2018.[115]

Swedish power metal band Sabaton‘s 2019 album The Great War contained a track titled “82nd All the Way”, a tribute to York’s Medal of Honor action.[116]

See also[edit]

- List of Medal of Honor recipients for World War I

- List of members of the American Legion

- List of people from Tennessee

- List of people on stamps of the United States

Notes[edit]

- ^ Owens, Ron (2004). Medal of Honor: Historical Facts & Figures. Turner Publishing Company. ISBN 9781563119958. Archived from the original on October 14, 2019. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

Exclusive of the five Marines who earned double awards of the Medal, Lt. Samuel Parker was the most highly decorated soldier of WWI.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c New York Times: Sergeant York, War Hero, Dies”, September 3, 1964, accessed September 20, 2010

- ^ Gregory, James (Summer 2020). “Forgotten Soldiers: The Other 16 at Chatel-Chehery”. Infantry Magazine. 109: 39–43.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Legends and Traditions of the Great War: Sergeant Alvin York by Dr. Michael Birdwell.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Laughter & Lawter Genealogy: Gladys Williams, “Alvin C. York”, accessed September 20, 2010 Archived October 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sergeant York and His People By Sam Kinkade Cowan page 85

- ^ York Indian Heritage at ancestry.com

- ^ Alvin York: A New Biography, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Lee, 1985, 9–13

- ^ Lee, 1985, 15–6

- ^ Capozzola, 2008, p. 67

- ^ Capozzola, 2008, p. 68, includes a photograph of York’s Registration Card from the National Archives

- ^ “Claim of Appeal for Conscientious Objector Status by Alvin Cullum York”

- ^ Jump up to:a b Capozzola, 2008, pp. 67–9

- ^ Sergeant York Patriotic Foundation: “Sgt. Alvin C. York’s Diary: November 17, 1917” Archived November 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, accessed September 21, 2010

- ^ Lee, 1985, 18–20

- ^ The events of the day are recounted in brief in Official History of the 82nd Division: American Expeditionary Forces, “All American” Division, 1917–1919 (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1919), 60–62; available online, accessed September 20, 2010

- ^ York 1930.

- ^ Lee, 1985, 25–6

- ^ Gregory, James (Summer 2020). “Forgotten Soldiers: The Other 16 at Chatel-Chehery”. Infantry Magazine. 109: 39–43.

- ^ Sergeant York Patriotic Foundation: “Sgt. Alvin C. York’s Diary: October 8, 1918” Archived November 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, accessed September 21, 2010

- ^ Buxton, G. Edward (1919). Official History of 82nd Division American Expeditionary Forces. The Bobbs-Merrill Company. pp. 58–62.

- ^ Lee, 1985, 32–6

- ^ Mastriano, Douglas, Colonel, U.S. Army Brave Hearts under Red Skiesand Douglas Mastriano: “A Day for Heroes” Archived December 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, accessed September 21, 2010

- ^ Lee, 1985, 39

- ^ “York, Alvin C. (Medal of Honor citation)”. Medal of Honor recipients — World War I. United States Army Center of Military History. June 8, 2009. Archived from the original on September 1, 2010. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ Mastriano, Douglas. “Trust Amidst Doubt and Adversity”. The Sergeant York Discovery Expedition. Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved January 27, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lee, American National Biography (2000)

- ^ Perry, John (2010). Sergeant York. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, Inc. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-59555-025-5.

- ^ “Be It Ever So Humble”. Underwood & Underwood. June 7, 1919. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ^ Lee, 1985, 53–5

- ^ Lee, 185, 58–60

- ^ Lee, 185, 60–62

- ^ Lee, 1985, 62–4

- ^ Lee, 1985, 63–4, 74–5

- ^ Lee, 1985, 64, 71–4, quote 73; “Hero York Harassed, Can’t Make Farm Pay”. New York Times. July 21, 1921. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ Lee, 1985, 76

- ^ Lee, 1985, 75–90. On the political context of the disputes about school funding, see David D. Lee, Tennessee in Turmoil: Politics in the Volunteer State, 1920–1932 (Memphis State University Press, 1979) ISBN 0-87870-048-X

- ^ “Education: Fentress Feud, May 25, 1936”. Time. May 25, 1936. Archived from the original on December 15, 2008. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ Cumberland Mountain State Park: A Civilian Conservation Corps Legacy at You Tube

- ^ Van West, Carroll (2001). Tennessee’s New Deal Landscape: A Guidebook. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-57233-107-5.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Mastriano, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d David E. Lee, Sergeant York: An American Hero (Lexington, 1985). ISBN 0-8131-1517-5

- ^ “Sergeant York Signs Up Again”. Life. Vol. 12. May 11, 1942. p. 26+. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Birdwell, Michael E. “Sergeant York and World War II” (PDF). Sergeant York. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 3, 2011. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ^ Lee, 1985, 116–20

- ^ Barry M. Stentiford, The American Home Guard: The State Militia in the Twentieth Century (Texas A & M University Press, 2002), 94 ISBN 1-58544-181-3; available online, accessed September 20, 2010

- ^ “Sgt. York Urges Aid for Red Cross”. New York Times. February 19, 1942. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ Lee, 1985, 93–4

- ^ New York Times: “Tennessee’s War Hero”, July 16, 1922, accessed September 20, 2010. Review of (Cowan, Sam K. (1922). Sergeant York And His People.). Called “worthwhile”, adding “careful restraint is one of its charms”, and objecting “The attempt to picture him as tearfully prayerful as he fought against merciless butchers for his own life and the lives of his American comrades verges on to mawkish twaddle.”

- ^ New York Times: “Tom Skeyhill, Author, Dies in Plane Crash”, May 23, 1932, accessed September 20, 2010, calls Skeyhill the author of York’s “official biography.”

- ^ Lee, 1985, 94–5

- ^ New York Times: S. T. Williamson, “Sergeant York Tells His Own Story”, December 23, 1928, accessed September 20, 2010, review of Sergeant York: His Own Life Story and War Diary, edited by Tom Skeyhill (NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1928). On Williamson see New York Times: “Samuel T. Williamson, 70, Dies”, June 19, 1962, accessed September 20, 2010. Skeyhill wrote a version for children Sergeant York: Last of the Long Hunters (John C. Winston Company, 1930)

- ^ New York Times: “Hull ‘Nominated’ on Tennessee Day”, July 23, 1939, accessed September 20, 2010

- ^ Lee, 1985, xi–xii

- ^ Lee, 1985, 101–2

- ^ Lee, 1985, 102–4

- ^ The story that York insisted on Gary Cooper in the title role derives from the fact that producer Jesse L. Lasky, who wanted Cooper for the role, recruited Cooper by writing a plea that he accept the role and then signing York’s name to the telegram. Lee, 1985, 105ff.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Plot Synopsis”. Allmovie. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ Lee, 1985, 114

- ^ Lee, 1985, 110

- ^ Lee, 1985, 110–1

- ^ “Cinema: New Picture, Aug. 4, 1941”. Time. August 4, 1941. Archived from the original on June 22, 2010. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ “Sergeant York (1941)”. Internet Movie Database. Archived from the original on July 29, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- ^ Lee, 1985, 128–9

- ^ Lee, 1985, 113, 128

- ^ Lee, 1985, 58, 67

- ^ Lee, 1985, 100

- ^ Lee, 1985, 100–1; New York Times: “Sergeant York Hopes We Will Avoid Wars”, November 11, 1934, accessed September 14, 2010; New York Times: “Peace to be Theme on Armistice Day”, November 9, 1936, accessed September 14, 2010

- ^ Lee, 1985, 120

- ^ Lee, 1985, 109–10. FDR quoted York’s speech at length in an address to the nation on November 11, 1941. See also Time: “Army & Navy and Civilian Defense: Old Soldiers”, May 18, 1942, accessed September 14, 2010

- ^ Lee, 1985, 109

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lee, 1985, 125

- ^ Lee, 1985, 132

- ^ Lee, 1985, 150 n31. G. Edward Buxton was York’s battalion commander in the 328th Infantry.

- ^ “Obituary, George E. York”. Jennings Funeral Home. Jamestown, TN. January 7, 2018.

- ^ “Constable Thomas Jefferson York”. The Officer Down Memorial Page.

- ^ New York Times: “Sergt. York Home, His Girl Says ‘Yes'”, June 1, 1919, accessed September 20, 2010

- ^ Lee, 1985, 127, 133–4

- ^ Time said he weighed 275 in 1941. “Cinema: New Picture, Aug. 4, 1941”. Time. August 4, 1941. Archived from the original on June 22, 2010. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ Lee, 1985, 134

- ^ Brown, Kenneth Rev. (1980). A Goodly Heritage: a History of the Churches of Christ in Christian Union. Circleville, OH: Circle Press, Inc. p. 122. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015 – via Wayback Machine.

- ^ Fontenay, Charles L. (September 28, 1984). “Sgt. York’s Widow Dies; Rites Set”. The Tennessean. Nashville, TN. p. 2B – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mastriano, p. 153.

- ^ Talley, Robert (November 11, 1929). “Eleven Years After War Finds Members in Different Jobs: Still Can’t Understand why Sergeant York Got all the Credit for Winning” (PDF). Niagara Falls Gazette. Niagara Falls, NY. p. 4.

- ^ Talley, Robert (November 11, 1929). “Controversy Still On Between Members Of Heroic Band of Soldiers In Argonne Fight” (PDF). Niagara Falls Gazette. Niagara Falls, NY. p. 4. Retrieved February 10, 2018 – via Fulton History.com.

- ^ Mastriano, Douglas (March 14, 2017). “Alvin York: Hero of the Argonne”. History Net.com. Leesburg, VA: Weider History Group.

- ^ Krimsky, George (May 5, 2008). “Move over, Sgt. York”. The Republican-American. Waterbury, CT. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ International News Service (October 5, 1929). “Sergeant Early to get Distinguished Service Cross Today”. The Kane Republican. Kane, PA. p. 1.

- ^ Associated Press (September 20, 1965). “Medal Comes 47 Years Late: “York and I fought Side by Side””. The Daily Citizen. Tucson, AZ. p. 33.

- ^ Smith, Craig S. (October 26, 2006). “Proof offered of Sergeant York’s war exploits”. The New York Times. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Montgomery, Nancy (May 26, 2008). “Officer says he’s pinpointed Sgt. York’s stand: 5,000 artifacts and exhausting research help American zero in on where a marker will be”. Stars and Stripes. Washington, DC.

- ^ Mastriano, Col. Douglas. “The York Artifacts Gallery”. www.sgtyorkdiscovery.com. Self-published. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ Tom Nolan (November 17, 2008). “Search for Sgt. York site turns into modern media battle” (PDF). The Record (Middle Tennessee State University). Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- ^ “Sergeant York Project – Saluting History of Greatness”. Sergeant York Project.

- ^ University of South Caroline: James B. Legg, “Finding Sgt. York”, 18–21 Archived June 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, accessed June 13, 2010

- ^ Texas State University: Nolan, “Battlefield Landscapes” Archived July 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, accessed June 13, 2010

- ^ Kelly, Michael (2018). Hero on the Western Front: Discovering Alvin York’s WWI Battlefield. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-52670-075-9.

- ^ “Tennessee Valley Healthcare System – Alvin C. York (Murfreesboro) Campus”. United States Department of Veterans Affairs. Archived from the original on September 3, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ “York Institute: Student Handbook 2007–2008”. York Institute Student Handbook. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ^ Pollak, Michael (August 7, 2005). “The Great Race – “A Tennesseean Honored””. The New York Times. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- ^ Lee, 1985, 130–2; Maxwell Geismar (August 22, 1943). “The Pattern of Dry Rot in Dixie”. The New York Times. Retrieved September 12, 2010.; Orville Prescott (August 24, 1959). “Books of The Times”. The New York Times. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ Robert Ewing Corlew, Stanley John Folmsbee, and Enoch L. Mitchell, Tennessee: A Short History, 2nd ed. (Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 1981), 442

- ^ Wilentz, Amy (September 9, 1985). “No More Time for Sergeant York”. Time. Archived from the original on December 7, 2009. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- ^ “Jeff Alexander’s House of Checklists: Congressional Medal of Honor, Eclipse, 1993”. Retrieved October 21, 2017.

- ^ Ford, Spc. Keisha (May 5, 2000). “The Pentagram: U.S. Postal Service salutes four American war heroes”. Center of Military History. U.S. Army. Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- ^ Kindred, Dave (June 21, 2004). “A proud performer after all”. The Sporting News. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- ^ “Laura Cantrell Biography”. Matador Records. June 21, 2005. Archived from the original on November 15, 2007. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- ^ “Ft Bragg – York Theatre”. Army and Air Force Exchange Service (AAFES). Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- ^ Scott, Marlon (October 23, 2007). “The New Sergeant York Trophy Series”. The All State. Retrieved October 23, 2007.

- ^ “OVCSports.com – Sgt. York Trophy presented by Delta Dental of Tennessee”. ovcsports.com. Retrieved October 9, 2015.

- ^ University of Texas: “Cadet Ribbons”, accessed November 21, 2010; Awarded to the cadet who does the most to support the ROTC program. Archived October 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Waymarking.com: “ETSU Army ROTC 50th Anniversary – Johnson City”, accessed August 29, 2010

- ^ Tennessee State Guard, Third Regiment: “Mission”, accessed September 20, 2010

- ^ “AUSA Book Program”. December 17, 2015.

- ^ “82nd All the Way – Lyrics”.

References[edit]

- Birdwell, Michael E. (1999). Celluloid Soldiers: The Warner Bros. Campaign against Nazism. New York, N.Y.: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-9871-3.

- Capozzola, Christopher (2008). Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen. New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533549-1.

- Lee, David D. (2000)( “York, Alvin Cullum” American National Biography (online 2000) online

- Lee, David D. (1985). Sergeant York: An American Hero. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1517-5.

- Mastriano, Douglas V. (2014). Alvin York: A New Biography of the Hero of the Argonne. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813145198. OCLC 858901754.

- Perry, John (1997). Sgt. York: His Life, Legend & Legacy. B&H Books. ISBN 0-8054-6074-8.

- Toplin, Robert Brent (1996). History by Hollywood: The Use and Abuse of the American Past. Chicago, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02073-1.

- Wheeler, Richard, ed. (1998). Sergeant York and the Great War. Bulverde, Tex.: Mantle Ministries. ISBN 1-889128-46-5.

- Williams, Gladys. “Alvin C. York”. York Institute. Archived from the original on March 26, 2005. Retrieved August 31, 2010.

Further reading[edit]

- Cowan, Sam K. (1922). Sergeant York And His People. Funk & Wagnall’s Company Project Gutenberg. online free

- Kelly, Jack (2007). “How Sergeant York Became America’s Hero”. American Heritage. Archived from the original on January 12, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- Skeyhill, Thomas. Sergeant York: Last of the Long Hunters (1930);

- Yockelson, Mitchell. Forty-Seven Days: How Pershing’s Warriors Came of Age to Defeat at the German Army in World War I. New York: NAL, Caliber, 2016. ISBN 978-0-451-46695-2.

- York, Alvin C.; Skeyhill, Tom, eds. (1928). His Own Life Story and War Diary. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc. (published 1930). Retrieved July 19, 2015.

External links[edit]

| Library resources about Alvin C. York |

| Resources in your libraryResources in other libraries |

Official

General information

- “Alvin Cullum York”. Hall of Valor. Military Times.

- Alvin Cullum York (1887–1964) at Medal of Honor Recipients Portrayed On Film (lylefrancispadilla.com)

- Alvin C. York at IMDb

- Sergeant York Project

- The Sergeant York Discovery Expedition (SYDE)

- Works by or about Alvin York at Internet Archive

Portals:BiographyFilmLiteratureUnited StatesWorld War IAlvin York at Wikipedia’s sister projects:![]() Media from Commons

Media from Commons![]() Quotations from Wikiquote

Quotations from Wikiquote

- 1887 births

- 1964 deaths

- United States Army personnel of World War I

- United States Army personnel of World War II

- American community activists

- American conscientious objectors

- American diarists

- American people of English descent

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- American Protestants

- Burials in Tennessee

- Chevaliers of the Légion d’honneur

- Civilian Conservation Corps people

- Military personnel from Tennessee

- Organization founders

- People from Harriman, Tennessee

- People from Pall Mall, Tennessee

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre 1914–1918 (France)

- Recipients of the War Merit Cross (Italy)

- Tennessee Democrats

- United States Army Medal of Honor recipients

- United States Army soldiers

- World War I recipients of the Medal of Honor

- Deaths by intracerebral hemorrhage

- American anti-communists

Navigation menu

- Not logged in

- Talk

- Contributions

- Create account

- Log in

Search

Contribute

Tools

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Permanent link

- Page information

- Cite this page

- Wikidata item

Print/export

In other projects

Languages