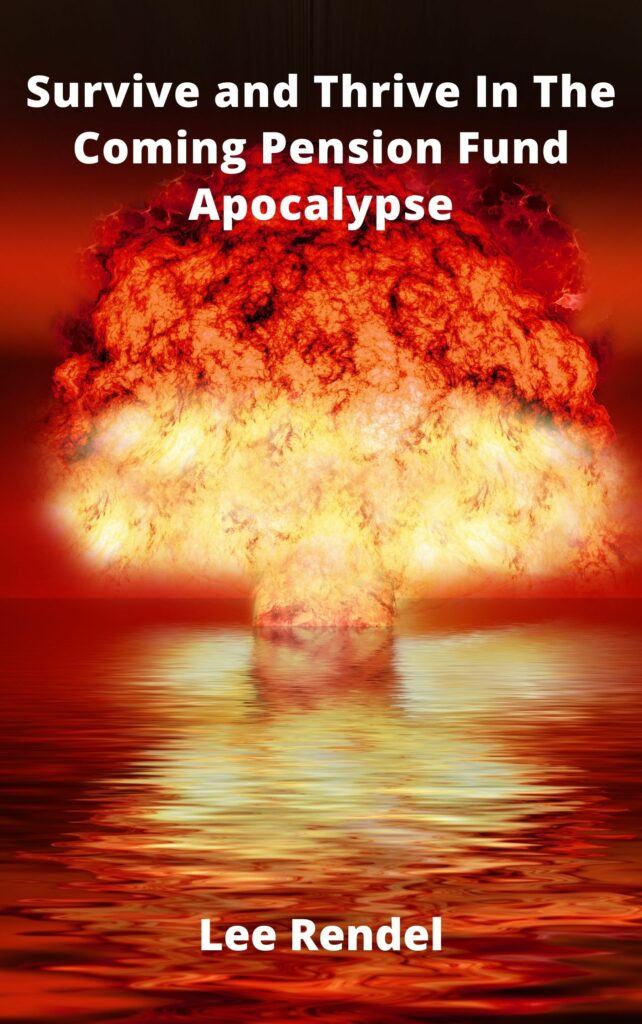

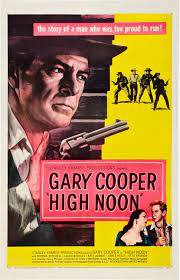

Gary Cooper

![]()

Gary Cooper

(46) Tex Ritter – High Noon – YouTube

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Gary cooper)Jump to navigationJump to searchFor other people named Gary Cooper, see Gary Cooper (disambiguation).

| Gary Cooper | |

|---|---|

| Cooper in 1952 | |

| Born | Frank James Cooper May 7, 1901 Helena, Montana, U.S. |

| Died | May 13, 1961 (aged 60) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Sacred Hearts Cemetery, New York, U.S. |

| Other names | Coop |

| Education | Grinnell College |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1925–1961 |

| Political party | Republican[1] |

| Spouse(s) | Veronica Balfe (m. 1933) |

| Children | 1 |

| Website | garycooper.com |

| Signature | |

Gary Cooper (born Frank James Cooper; May 7, 1901 – May 13, 1961) was an American actor known for his strong, quiet screen persona and understated acting style. He won the Academy Award for Best Actor twice and had a further three nominations, as well as receiving an Academy Honorary Award for his career achievements in 1961. He was one of the top 10 film personalities for 23 consecutive years and one of the top money-making stars for 18 years. The American Film Institute (AFI) ranked Cooper at No. 11 on its list of the 25 greatest male stars of classic Hollywood cinema.

Cooper’s career spanned 36 years, from 1925 to 1961 and included leading roles in 84 feature films. He was a major movie star from the end of the silent film era through to the end of the golden age of Classical Hollywood. His screen persona appealed strongly to both men and women, and his range of performances included roles in most major film genres. His ability to project his own personality onto the characters he played contributed to his natural and authentic appearance on screen. Throughout his career, he sustained a screen persona that represented the ideal American hero.

Cooper began his career as a film extra and stunt rider but soon landed acting roles. After establishing himself as a Western hero in his early silent films, he appeared as the Virginian and became a movie star in 1929 with his first sound picture, The Virginian. In the early 1930s, he expanded his heroic image to include more cautious characters in adventure films and dramas such as A Farewell to Arms (1932) and The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935). During the height of his career, Cooper portrayed a new type of hero—a champion of the common man—in films such as Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936), Meet John Doe (1941), Sergeant York (1941), The Pride of the Yankees (1942), and For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943). He later portrayed more mature characters at odds with the world in films such as The Fountainhead (1949) and High Noon (1952). In his final films, he played non-violent characters searching for redemption in films such as Friendly Persuasion (1956) and Man of the West (1958).

Contents

- 1Early life

- 2Career

- 3Personal life

- 4Final years and death

- 5Acting style and reputation

- 6Career assessment and legacy

- 7Awards and nominations

- 8Filmography

- 9Radio appearances

- 10References

- 11External links

Early life[edit]

Cooper dressed as a cowboy, 1903

Frank James Cooper was born in Helena, Montana, on May 7, 1901, the younger of two sons of English parents Alice (née Brazier; 1873–1967) and Charles Henry Cooper (1865–1946).[2] His brother, Arthur, was six years his senior. Cooper’s father came from Houghton Regis, Bedfordshire,[3] and became a prominent lawyer, rancher, and Montana Supreme Court justice.[4] His mother hailed from Gillingham, Kent, and married Charles in Montana.[5] In 1906, Charles purchased the 600-acre (240 ha) Seven-Bar-Nine cattle ranch,[6][7] about 50 miles (80 km) north of Helena near Craig, Montana.[8] Cooper and Arthur spent their summers at the ranch and learned to ride horses, hunt, and fish.[9][10] Cooper attended Central Grade School in Helena.[11]

Alice wanted her sons to have an English education, so she took them back to England in 1909 to enroll them in Dunstable Grammar School in Dunstable, Bedfordshire. While there, Cooper and his brother lived with their father’s cousins, William and Emily Barton, at their home in Houghton Regis.[12][13] Cooper studied Latin, French, and English history at Dunstable until 1912.[14] While he adapted to English school discipline and learned the requisite social graces, he never adjusted to the rigid class structure and formal Eton collars he was required to wear.[15] He received his confirmation in the Church of England at the Church of All Saints in Houghton Regis on December 3, 1911.[16][17] His mother accompanied her sons back to the U.S. in August 1912, and Cooper resumed his education at Johnson Grammar School in Helena.[11]

When Cooper was 15, he injured his hip in a car accident. On his doctor’s recommendation, he returned to the Seven-Bar-Nine ranch to recuperate by horseback riding.[18] The misguided therapy left him with his characteristic stiff, off-balanced walk and slightly angled horse-riding style.[19] He left Helena High School after two years in 1918, and returned to the family ranch to work full-time as a cowboy.[19] In 1919, his father arranged for him to attend Gallatin County High School in Bozeman, Montana,[20][21] where English teacher Ida Davis encouraged him to focus on academics and participate in debating and dramatics.[21][22] Cooper later called Davis “the woman partly responsible for [him] giving up cowboy-ing and going to college”.[22]Cooper at Grinnell College (top row, second from the left), 1922

Cooper was still attending high school in 1920 when he took three art courses at Montana Agricultural College in Bozeman.[21] His interest in art was inspired years earlier by the Western paintings of Charles Marion Russell and Frederic Remington.[23] Cooper especially admired and studied Russell’s Lewis and Clark Meeting Indians at Ross’ Hole (1910), which still hangs in the state capitol building in Helena.[23] In 1922, to continue his art education, he enrolled in Grinnell College in Grinnell, Iowa. He did well academically in most of his courses,[24] but was not accepted into the school’s drama club.[24] His drawings and watercolor paintings were exhibited throughout the dormitory, and he was named art editor for the college yearbook.[25] During the summers of 1922 and 1923, Cooper worked at Yellowstone National Park as a tour guide driving the yellow open-top buses.[26][27] Despite a promising first 18 months at Grinnell, he left college suddenly in February 1924, spent a month in Chicago looking for work as an artist, and then returned to Helena,[28] where he sold editorial cartoons to the local Independent newspaper.[29]

In autumn 1924, Cooper’s father left the Montana Supreme Court bench and moved with his wife to Los Angeles to administer the estates of two relatives,[30][31] and Cooper joined his parents there in November at his father’s request.[30] After briefly working a series of unpromising jobs, he met two friends from Montana[32][33] who were working as film extras and stunt riders in low-budget Western films for the small movie studios on Poverty Row.[34] They introduced him to another Montana cowboy, rodeo champion Jay “Slim” Talbot, who took him to see a casting director.[32] Wanting money for a professional art course,[30] Cooper worked as a film extra for $5 a day, and as a stunt rider for $10. Cooper and Talbot became close friends and hunting companions, and Talbot later worked as Cooper’s stuntman and stand-in for over three decades.[34]

Career[edit]

Silent films, 1925–1928[edit]

Cooper in The Winning of Barbara Worth, 1926Cooper in The Winning of Barbara Worth, 1926

In early 1925, Cooper began his film career in silent pictures such as The Thundering Herd and Wild Horse Mesa with Jack Holt,[35] Riders of the Purple Sage and The Lucky Horseshoe with Tom Mix,[36][37] and The Trail Rider with Buck Jones.[36] He worked for several Poverty Row studios, but also the already emergent major studios, Famous Players-Lasky and Fox Film Corporation.[38] While his skilled horsemanship led to steady work in Westerns, Cooper found the stunt work—which sometimes injured horses and riders—”tough and cruel”.[35] Hoping to move beyond the risky stunt work and obtain acting roles, Cooper paid for a screen test and hired casting director Nan Collins to work as his agent.[39] Knowing that other actors were using the name “Frank Cooper”, Collins suggested he change his first name to “Gary” after her hometown of Gary, Indiana.[40][41][42] Cooper immediately liked the name.[43][Note 1]

Cooper also found work in a variety of non-Western films, appearing, for example, as a masked Cossack in The Eagle (1925), as a Roman guard in Ben-Hur (1925), and as a flood survivor in The Johnstown Flood (1926).[36] Gradually, he began to land credited roles that offered him more screen time, in films such as Tricks (1925), in which he played the film’s antagonist, and the short film Lightnin’ Wins (1926).[45] As a featured player, he began to attract the attention of major film studios.[46] On June 1, 1926, Cooper signed a contract with Samuel Goldwyn Productions for fifty dollars a week.[47]

Cooper’s first important film role was a supporting part in The Winning of Barbara Worth (1926) starring Ronald Colman and Vilma Bánky,[47] in which he plays a young engineer who helps a rival suitor save the woman he loves and her town from an impending dam disaster.[48] Cooper’s experience living among the Montana cowboys gave his performance an “instinctive authenticity”, according to biographer Jeffrey Meyers.[49] The film was a major success.[50] Critics singled out Cooper as a “dynamic new personality” and future star.[51][52] Goldwyn rushed to offer Cooper a long-term contract, but he held out for a better deal—finally signing a five-year contract with Jesse L. Lasky at Paramount Pictures for $175 a week.[51] In 1927, with help from Clara Bow, Cooper landed high-profile roles in Children of Divorce and Wings (both 1927), the latter being the first film to win an Academy Award for Best Picture.[53] That year, Cooper also appeared in his first starring roles in Arizona Bound and Nevada—both films directed by John Waters.[54]

Paramount paired Cooper with Fay Wray in The Legion of the Condemned and The First Kiss (both 1928)—advertising them as the studio’s “glorious young lovers”.[55] Their on-screen chemistry failed to generate much excitement with audiences.[55][56][57] With each new film, Cooper’s acting skills improved and his popularity continued to grow, especially among female movie-goers.[57] During this time, he was earning as much as $2,750 per film[58] and receiving a thousand fan letters a week.[59] Looking to exploit Cooper’s growing audience appeal, the studio placed him opposite popular leading ladies such as Evelyn Brent in Beau Sabreur, Florence Vidor in Doomsday, and Esther Ralston in Half a Bride (also both 1928).[60] Around the same time, Cooper made Lilac Time (1928) with Colleen Moore for First National Pictures, his first movie with synchronized music and sound effects. It became one of the most commercially successful films of 1928.[60]

Hollywood stardom, 1929–1935[edit]

Cooper and Mary Brian in The Virginian, 1929

Cooper became a major movie star in 1929 with the release of his first talking picture, The Virginian (1929), which was directed by Victor Fleming and co-starred Mary Brian and Walter Huston. Based on the popular novel by Owen Wister, The Virginian was one of the first sound films to define the Western code of honor and helped establish many of the conventions of the Western movie genre that persist to the present day.[61] According to biographer Jeffrey Meyers, the romantic image of the tall, handsome, and shy cowboy hero who embodied male freedom, courage, and honor was created in large part by Cooper in the film.[62] Unlike some silent film actors who had trouble adapting to the new sound medium, Cooper transitioned naturally, with his “deep and clear” and “pleasantly drawling” voice, which was perfectly suited for the characters he portrayed on screen, also according to Meyers.[63] Looking to capitalize on Cooper’s growing popularity, Paramount cast him in several Westerns and wartime dramas, including Only the Brave, The Texan, Seven Days’ Leave, A Man from Wyoming, and The Spoilers (all released in 1930).[64] Norman Rockwell depicted Cooper in his role as The Texan for the cover of The Saturday Evening Post on May 24, 1930.[65]Lili Damita and Cooper in Fighting Caravans, 1931

One of the more important performances in Cooper’s early career was his portrayal of a sullen legionnaire in Josef von Sternberg‘s film Morocco (also 1930)[66] with Marlene Dietrich in her introduction to American audiences.[67] During production, von Sternberg focused his energies on Dietrich and treated Cooper dismissively.[67] Tensions came to a head after von Sternberg yelled directions at Cooper in German. The 6-foot-3-inch (191 cm) actor approached the 5-foot-4-inch (163 cm) director, picked him up by the collar, and said, “If you expect to work in this country you’d better get on to the language we use here.”[68][69] Despite the tensions on the set, Cooper produced “one of his best performances”, according to Thornton Delehanty of the New York Evening Post.[70]

After returning to the Western genre in Zane Grey‘s Fighting Caravans (1931) with French actress Lili Damita,[71] Cooper appeared in the Dashiell Hammett crime film City Streets (also 1931), co-starring Sylvia Sidney and Paul Lukas, playing a westerner who gets involved with big-city gangsters in order to save the woman he loves.[72] Cooper concluded the year with appearances in two unsuccessful films: I Take This Woman (also 1931) with Carole Lombard, and His Woman with Claudette Colbert.[73] The demands and pressures of making ten films in two years left Cooper exhausted and in poor health, suffering from anemia and jaundice.[67][74] He had lost thirty pounds (fourteen kilograms) during that period,[74][75] and felt lonely, isolated, and depressed by his sudden fame and wealth.[76][77] In May 1931, Cooper left Hollywood and sailed to Algiers and then Italy, where he lived for the next year.[76]

During his time abroad, Cooper stayed with the Countess Dorothy di Frasso at the Villa Madama in Rome, where she taught him about good food and vintage wines, how to read Italian and French menus, and how to socialize among Europe’s nobility and upper classes.[78] After guiding him through the great art museums and galleries of Italy,[78] she accompanied him on a ten-week big-game hunting safari on the slopes of Mount Kenya in East Africa,[79] where he was credited with over sixty kills, including two lions, a rhinoceros, and various antelopes.[80][81] His safari experience in Africa had a profound influence on Cooper and intensified his love of the wilderness.[81] After returning to Europe, he and the countess set off on a Mediterranean cruise of the Italian and French Rivieras.[82] Rested and rejuvenated by his year-long exile, a healthy Cooper returned to Hollywood in April 1932[83] and negotiated a new contract with Paramount for two films per year, a salary of $4,000 a week, and director and script approval.[84]Cooper and Helen Hayes in A Farewell to Arms, 1932

In 1932, after completing Devil and the Deep with Tallulah Bankhead to fulfill his old contract,[85] Cooper appeared in A Farewell to Arms,[86] the first film adaptation of an Ernest Hemingway novel.[87] Co-starring Helen Hayes, a leading New York theatre star and Academy Award winner,[88] and Adolphe Menjou, the film presented Cooper with one of his most ambitious and challenging dramatic roles,[88] playing an American ambulance driver wounded in Italy who falls in love with an English nurse during World War I.[86] Critics praised his highly intense and emotional performance,[89][90] and the film became one of the year’s most commercially successful pictures.[88] In 1933, after making Today We Live with Joan Crawford and One Sunday Afternoon with Fay Wray, Cooper appeared in the Ernst Lubitsch comedy film Design for Living, based on the successful Noël Coward play.[91][92] Co-starring Miriam Hopkins and Fredric March, the film was a box office success,[93] ranking as one of the top ten highest-grossing films of 1933. All three of the lead actors—March, Cooper, and Hopkins—received attention from this film as they were all at the peak of their careers. Cooper’s performance — playing an American artist in Europe competing with his playwright friend for the affections of a beautiful woman — was singled out for its versatility[94] and revealed his genuine ability to do light comedy.[95] Cooper changed his name legally to “Gary Cooper” in August 1933.[96]Anna Sten and Cooper in The Wedding Night, 1935

In 1934, Cooper was loaned out to MGM for the Civil War drama film Operator 13 with Marion Davies, about a beautiful Union spy who falls in love with a Confederate soldier.[97] Despite Richard Boleslawski‘s imaginative direction and George J. Folsey‘s lavish cinematography, the film did poorly at the box office.[98]

Back at Paramount, Cooper appeared in his first of seven films by director Henry Hathaway,[99] Now and Forever, with Carole Lombard and Shirley Temple.[100] In the film, he plays a confidence man who tries to sell his daughter to the relatives who raised her, but is eventually won over by the adorable girl.[101] Impressed by Temple’s intelligence and charm, Cooper developed a close rapport with her, both on and off screen.[99][Note 2] The film was a box-office success.[98]

The following year, Cooper was loaned out to Samuel Goldwyn Productions to appear in King Vidor‘s romance film The Wedding Night with Anna Sten,[102] who was being groomed as “another Garbo“.[103][104] In the film, Cooper plays an alcoholic novelist who retreats to his family’s New England farm where he meets and falls in love with a beautiful Polish neighbor.[102] Cooper delivered a performance of surprising range and depth, according to biographer Larry Swindell.[105] Despite receiving generally favorable reviews,[106] the film was not popular with American audiences, who may have been offended by the film’s depiction of an extramarital affair and its tragic ending.[105]

That same year, Cooper appeared in two Henry Hathaway films: the melodrama Peter Ibbetson with Ann Harding, about a man caught up in a dream world created by his love for a childhood sweetheart,[107] and the adventure film The Lives of a Bengal Lancer, about a daring British officer and his men who defend their stronghold at Bengal against rebellious local tribes.[108] While the former, championed by the surrealists[109] became more successful in Europe than in the United States, the latter was nominated for seven Academy Awards[110] and became one of Cooper’s most popular and successful adventure films.[111][112] Hathaway had the highest respect for Cooper’s acting ability, calling him “the best actor of all of them”.[99]

American folk hero, 1936–1943[edit]

From Mr. Deeds to The Real Glory, 1936–1939[edit]

Cooper and Jean Arthur in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936

Cooper’s career took an important turn in 1936.[113] After making Frank Borzage‘s romantic comedy film Desire with Marlene Dietrich at Paramount—in which he delivered a performance considered by some contemporary critics as one of his finest[113]—Cooper returned to Poverty Row for the first time since his early silent film days to make Frank Capra‘s Mr. Deeds Goes to Town with Jean Arthur for Columbia Pictures.[114] In the film, Cooper plays the character of Longfellow Deeds, a quiet, innocent writer of greeting cards who inherits a fortune, leaves behind his idyllic life in Vermont, and travels to New York where he faces a world of corruption and deceit.[115] Capra and screenwriter Robert Riskin were able to use Cooper’s well-established screen persona as the “quintessential American hero”[113]—a symbol of honesty, courage, and goodness[116][117][118]—to create a new type of “folk hero” for the common man.[113][119] Commenting on Cooper’s impact on the character and the film, Capra observed:

As soon as I thought of Gary Cooper, it wasn’t possible to conceive anyone else in the role. He could not have been any closer to my idea of Longfellow Deeds, and as soon as he could think in terms of Cooper, Bob Riskin found it easier to develop the Deeds character in terms of dialogue. So it just had to be Cooper. Every line in his face spelled honesty. Our Mr. Deeds had to symbolize uncorruptibility, and in my mind Gary Cooper was that symbol.[120]

Both Desire and Mr. Deeds opened in April 1936 to critical praise and were major box-office successes.[121] In his review in The New York Times, Frank Nugent wrote that Cooper was “proving himself one of the best light comedians in Hollywood”.[122] For his performance in Mr. Deeds, Cooper received his first Academy Award nomination for Best Actor.[123]Cooper and Jean Arthur in The Plainsman, 1936

Cooper appeared in two other Paramount films in 1936. In Lewis Milestone‘s adventure film The General Died at Dawn with Madeleine Carroll, he plays an American soldier of fortune in China who helps the peasants defend themselves against the oppression of a cruel warlord.[124][125] Written by playwright Clifford Odets, the film was a critical and commercial success.[124][126]

In Cecil B. DeMille‘s sprawling frontier epic The Plainsman—his first of four films with the director—Cooper portrays Wild Bill Hickok in a highly fictionalized version of the opening of the American western frontier.[127] The film was an even greater box-office hit than its predecessor,[128] due in large part to Jean Arthur’s definitive depiction of Calamity Jane and Cooper’s inspired portrayal of Hickok as an enigmatic figure of “deepening mythic substance”.[129] That year, Cooper appeared for the first time on the Motion Picture Herald exhibitor’s poll of top ten film personalities, where he would remain for the next twenty-three years.[130]